November 22, 2016 in Bishop, Faith in action

Marking an African-American Lutheran Pioneer

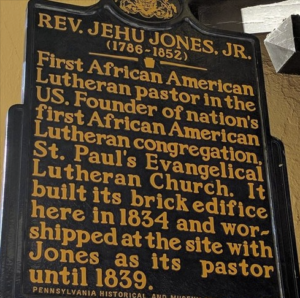

Lutherans gathered on Quince Street Nov. 19 to dedicate a new state historical marker honoring the Rev. Jehu Jones Jr., who was ordained the first African-American Lutheran pastor in 1832 and founded the first African-American Lutheran congregation two years later.

“Today we gather to celebrate a pioneer of both radical racial and ecumenical partnership…who persevered against all sabotage, segregation, and setbacks of his time and of his people,” Bishop Claire Burkat said during her remarks at the service.

Pastor Jones served faithfully “in spite of a yoke of racism and trying circumstances that none of us standing here will ever understand,” the bishop said. Jones was “a pastor who did not submit to a yoke of oppression even for a moment” so that Christ was proclaimed, she said.

“I am here as a Lutheran Church historian to remind all of us that Black Lutheran lives matter,” said the Rev. Dr. Timothy J. Wengert, emeritus professor at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia.

“We live in perilous times” under a renewed specter of racism, Wengert said, “and the arc of justice seems much longer than it did eight years ago.”

“What we’re dedicated to here is precisely that arc and that movement toward justice,” he said.

- Scroll down to watch video of the ceremony

The marker is erected outside the University of Pennsylvania’s Mask & Wig Club at 310 Quince Street, the site of the former St. Paul’s Colored Lutheran Church. Though the original structure has been modified, the original worship space upstairs is largely unchanged and the original cornerstone is displayed in the vestibule of the theater.

Rev. Jones was born enslaved in Charleston, S.C., in 1786. He joined St. John’s Lutheran Church there in 1820 and in 1832 travelled to New York where the ministerium ordained him to be a missionary to freed slaves in Liberia. Returning to Charleston he ran afoul of a law aimed at returning freedmen and he relocated his family to Philadelphia, where he was appointed a missionary to the city’s Black population, according to retired LTSP Professor Richard Stewart.

Jones received a frosty reception, and Stewart says a fellow Lutheran pastor told Jones he would never be accepted because of his color.

Jones received a frosty reception, and Stewart says a fellow Lutheran pastor told Jones he would never be accepted because of his color.

In 1834 the new St. Paul’s congregation laid the cornerstone for the building on this site, which was then labeled 150 S. Quince Street. During this time Jones traveled a circuit that took him to Harrisburg, Gettysburg and Chambersburg, ministering to more than 2,700 African-American families.

In 1838, community leaders described by Jones as “respected white gentlemen” offered to pay the church mortgage if they assigned ownership to them. These backers apparently did not pay the mortgage, and the church was sold at sheriff’s sale in 1839. Rev. Jones continued to lead the congregation for some years.

Rev. Jones was active in Philadelphia African American congregations as well as Pennsylvania politics, and the national Colored Conventions Movement through at least 1851, the year before his death. He and St. Paul’s congregation were also active in the Moral Reform and Improvement Society, a group of African American churches whose goal was to improve the social conditions for blacks in Philadelphia.

The location of St. Paul’s and the significance of Rev. Jones’ contributions were revealed by research by Karl Earl Johnson, a graduate student at LTSP, in the 1990s. LTSP held the first public commemoration of Rev. Jones at a communion service in 1995. Wengert said he hopes that the Lutheran Church will eventually include Rev. Jones in its list of commemorations and offer national recognition.

As a result of work by Johnson, Stewart and Wengert, the state erected a marker on the site in 1997, which subsequently went missing. The Philadelphia Chapter of the African Descent Lutheran Association worked to have the marker re-installed.

“We pledge to keep putting it up every single time it is taken down for whatever reason…in remembrance of all, not just Rev. Jones, who persevered for justice, and mercy, and reconciliation among people of all races,” Bishop Burkat said.